‘The Rules’ exhibition examines the rulesets of machines, humans and social organisations. The central topics are the rules of computers and their transformatory effects on the processes of our society. Software produces new ways of behaviour and new realities. This results in a critical responsibility when we are using digital tools, but also in new opportunities for design.

‘The Rules’ exhibition shows work from selected international artists and from the NODE open call. The pieces render visible ideas of ‘The Rules’ as design matter. This is either through the creation of their own rules within the realm of the artistic piece, or in critical relation to existing rule systems such as computer networks or conventions of the art world.

The works are arranged around the primary use of the Kunstverein as the NODE academy and knowledge exchange forum. This shortcut between production and product makes the underlying nature of some of the works that use software as a core component transparent to the general public.

The exhibition is an informal collection of work relevant for the ‘The Rules’ theme and to the Zeitgeist of the festival audience. And there’s also an exit through the giftshop: The exhibition is open parallel to artist talks and performances.

In her sound installation ‘Fabricmachine’, Kathrin Sturmreich interprets textile fabric as a sound-on-film track. Using an optical sensor, she translates the moving structure of fabric panels into a rhythmic soundscape. This installation reduces one of the earliest digital applications, the automatic industrial production of weaving patterns, to a state of sensual perception. The fabrics are arranged not for their fashionable value but as notation of a multi-layered sound collage.

When looking at Geoffrey Lillemon’s work, we may first think of disgust, voyeurism, infantility or white trash cultural pessimism. However, there’s more going on: by mixing human desires with the coldness of technology rather drastically, he creates the possibility that replicas of human beings might not be ‘uncanny’* any more. It seems that human instincts have to be adjusted to the digital world first. Lillemon uses representations from the recent history of art in order to show where humanness within the digital world might be found in the future. Zombies couldn’t be any less zombie-like than this.

* ‘uncanny’ describes the phenomenon that digital human replicas look almost, but not perfectly, like actual human beings.

Memo Akten establishes an audio-visual rule book, which is executed until it comes to a full circle and closes in. Following the easiest principles of harmony with calculable predictability, it unfolds into a complex composition. This mathematical production creates both image and sound. The viewer’s perception constantly switches between both mediums, so that he or she cannot tell if the image causes or follows the sound. This synaesthetic physicality gives a certain plausibility to the objects.

Kohlberger’s work ‘Humming, Fast and Slow’ is an interference between the analogue and the digital. It operates on the line that was defined as the absolute threshold of visual perception. 60 hertz, 24bit colours and a few million pixels should suffice to create the illusion of a continuous event. Kohlberger employs a buzzing, both visual and acoustic, that fills the whole range of this definition in order to make the threshold itself disappear. Analogue disparity and digital continuum merge.

It is impossible to decide which part of this project by Polish design studio ‘Noviki Studio’ could be regarded as art, design, mediation or a repository of creative work.

The website najlepszewystawy.pl serves not just as a platform for announcements but also as a part of an survey about artists’ and curators’ dream projects, which was conducted in a plethora of formats – as an exhibition, book, exhibitions about exhibitions, and as this very website.

The entire project is interesting in the context of ‘The Rules’ in several respects. On the one hand, the authors question the rules of distribution of art by revealing the network of relations behind it.

On the other hand, Mark Leckey’s exhibition concept ‘Techgnosis’, which is presented on the website, illustrates the relationship between machinery and mind, and between humans, animals and machines.

This complex and fluctuating meaning is mirrored in the project’s generative appearance.

Gabriel Shalom and Patrizia Kommerell’s (KS12) stories switch between fact and fiction. Their video essays, which mainly consist of interviews, experiment with new forms of narration, which originate from modes of production and association found in a digitally linked community. NODE13 commissioned KS12’s new work, which has been produced under the title ‘Another Dimension’ as a part of the Deutsche Börse Residency programme in Frankfurt.

Screens are a frame of reference for a society that’s constantly staring at visual display units. Our fantasies and dreams create the worlds that are hidden behind this layer of glass in a plastic frame. A large pat of contemporary culture takes place beneath this glassy surface, and even when they are switched off, screens act as status symbols in our apartments and offices. A large number of everyday tasks are motivated out of these square boxes. By replacing the ‘screen family’ with mirrors, Rozendaal unmarks this frame of reference and exposes its true character – a mirror.

This could be read as a moralistic commentary, but an essential part of Rozendaal’s creative work operates within this frame of reference: Rozendaal demonstrates that appearance and inauthenticity can assume a convincing and coercive position on art.

Kyle McDonald and Elliot Woods are invited to create a site-specific installation on the 4th floor of the Frankfurter Kunstverein. Their work is still in progress at this time and we are curious of what to expect.

Especially in the context of vvvv Robert Mathy’s work reveals itself to the visitor: Something’s happening at the end of each line. His sound sculpture ‘Volume’ puts this visual grammar into the centre of the exhibition ‘The Rules’. The motors are connected to a ‘black box’, which acts as their control system. Using this ‘instrument’, Mathy designs a spatial composition from the objects and material he finds.

Discovered in June 2010, the Stuxnet Virus is considered a major cyber weapon.

Initially spreading via Microsoft Windows, it targets industrial software and equipment and is the first discovered malware that spies on and subverts industrial systems. Its primary target is the Siemens Simatic S7-300 PLC CPU, commonly found in large scale industrial sites, including Nuclear Facilities.

Solitary Confinement is a small, non-interactive installation comprising a simple, unmarked computer, without screen or keyboard, that has been deliberately infected with the Stuxnet Virus. It sits in a vitrine, powered on, with one end of an Ethernet cable laying unplugged near the Ethernet port. The vitrine cover is unscrewed and warning tape delineates a ‘no-touch’ zone on the floor.

Here the visible state of disconnection evokes both a volatile, techno-political tension and an aura of anxiety. Stuxnet, one of the world’s most dangerous works of software, needs only a connection to the Internet to continue its destructive quest.

Julian Oliver examines the structures of the power of technical systems over people and people’s dependency on them. Co-author of the ‘Critical Engineering Manifesto’, he envisions the image of an engineer-activist, whose task is to identify technocratic structures and undermine them. The mediums of these subversive strategies are the very objects and operations of technology themselves. They are used to attack the reigning technological economy and are meant to reverse the relationship between the producers and consumers of technology. Two of Julian Oliver’s works are part of the exhibition.

Every technology produces its own surface and artefacts and therefore constitutes a medium on its own. If we discover faults on a perfect surface, we may get the impression of looking into the medium and seeing its true self. The glitched images by Daniel Schwarz force viewers to interrogate how technology changes our understanding of time, space and place.

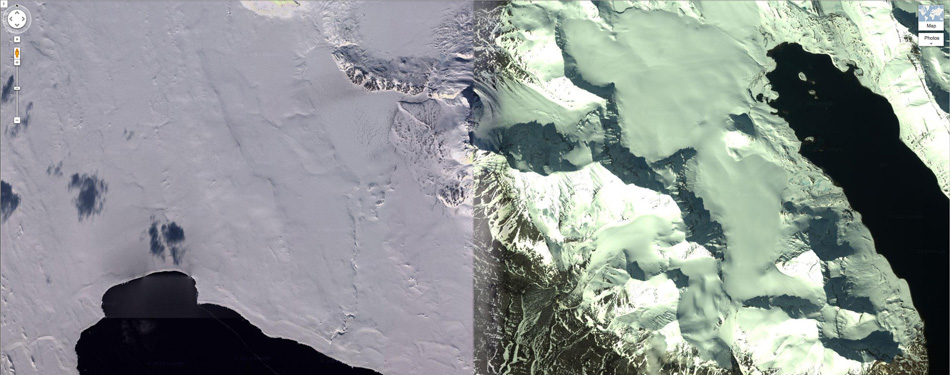

‘Juxtapose’ is a series of images taken directly from Google Maps that expose distant places, far from society, shown simultaneously under the force of contrary seasons and weather phenomena at varying times.

The images arise from glitches which are created automatically when Google Maps’ algorithm stitches images of updated photos with previously recorded ones together in a grid-like view.

Evy Schubert manages to visualize the relationship between political structures, and social rules respectively, as well as her personal emotional state in the most compact of settings, a thumbnail video installation.

Schubert’s ‘Zelebration postsowjetischer Hörigkeit’ (celebration of post-soviet bondage) adapts a vision put forth by German sociologist Max Weber that every individual is ruled by the exterior rational, bureaucratic and capitalistic forces of modern states. In this video performance, this fear is connected to the sentient individual lost in the post-soviet state of imprisonment and inflexibility,where the bondage of old rules competes with the demands of western economic and democratic state systems.

Routinely and efficiently, Gabriel Hošovský paves the way to his own downfall as he cuts off the branches he is sitting on. An understandable practice, it seems, for those who have lived behind the Iron Curtain.

These performances, which are enacted in a post-Soviet scenario, affect the viewer as if they were the alarming message of a worldly-wise man. It doesn’t matter if the rhetorics of socio-economic crises prove to be correct or not – or if we are going to act as clever as he does – Hošovský’s rule #1 says: ‘Life goes on.’

Using a semi-automatic scanning method, Ivo Schüssler created 3D objects from stones he found on his hiking-tours, so that they could exist as avatars in digital space. It is simple enough to understand the change in the state of being that they have undergone by being disembodied and transferred into the space of digital representation. The stone loses its stoniness and a new, more ideal ‘state of being’ emerges. The stone is no longer a stone.

Matisse has made this process of signification of art comprehensible with his famous painting ‘Ceci n’est pas une pipe’ (‘This is not a pipe’). However, this process takes a new turn when it undergoes automatic treatments as a part of its digitalization, which becomes apparent in Schüssler’s work.The digital space has a certain autonomy of adaption, realization and memorization that doesn’t exist in traditional forms of representation. Though the viewer remains the centre of reference for Matisse, this approach suggests that things in digital form are part of their own reality, and they no longer need a human spectator to be realized.